Running a rescue centre and a number of live educational displays takes a lot of effort, small but invaluable daily tasks of proper animal husbandry, and (among other things) resources. From feed for the animals to energy to run the entire facility, the cogs and gears that keep an organization this big running are often overlooked, but critically important. After working at the Kadoorie Farm for a few weeks, we began to wonder where it all came from, so we did some investigating.

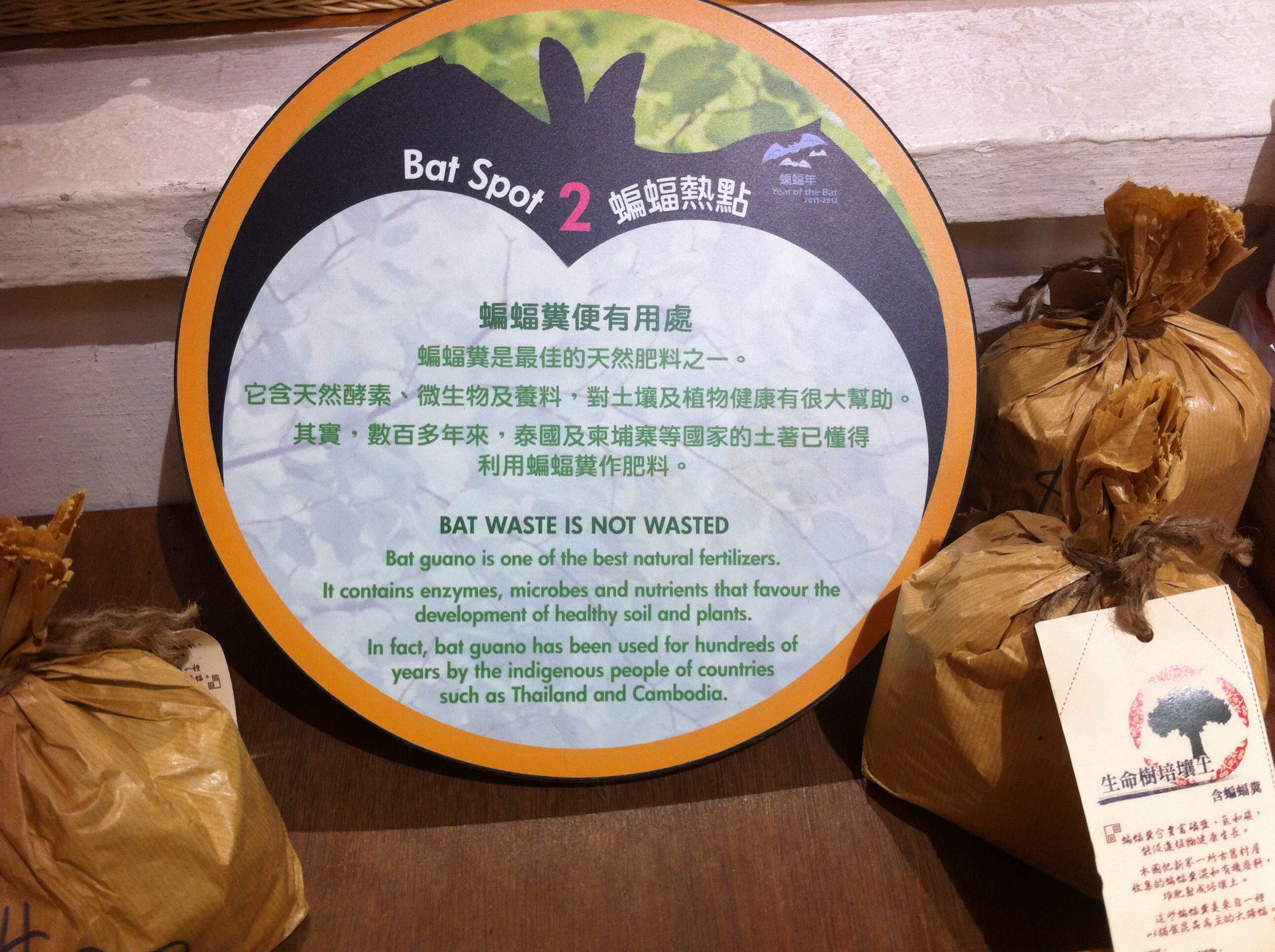

Both animals, staff and visitors are fed primarily with produce and product grown on the farm. Both the Sun Garden Cafe and The Farm Shop offer a wonderful selection of vegetables, grains, and eggs which are either locally grown or harvested from the farm itself, as well as various fertilizers for people’s own backyard gardens or farms.

The agricultural part of the farm still grows crops, and there is also an eco-garden to teach visitors about growing their own food, along with a employee garden so staff can grow their own food and grab a snack on the go.

In addition to this, the Cafe uses no disposable utensils, napkins, or take-away containers. Both of these small, but important strategies decrease the damage caused to the environment by the use of fossil fuels in transportation. The lack of disposable cutlery cuts down on the amount of garbage produced, as well as waste which can cause harm to animals who consume it, and would increase the space needed for huge dump sites – further destroying animal (and human) habitats. There is very little recycling in Hong Kong, and the places who do accept recyclable waste have to ship it all the way to mainland China to be processed. The landfills here are overflowing (as is true of most heavily populated areas in the world), but instead of managing waste with recycling programs, and green bins for organic waste Hong Kong has recently licensed an incinerator in Tuen Mun. This quick fix will have huge impacts on both local citizens and the environment by raising the regional temperature by 1-2 degrees Celsius and increasing fume emissions detrimentally leading to more greenhouse gasses and higher risk of lung cancer in humans and animals (Terry Li Kwai Fong).

In the abstract, eating and growing food locally strengthens the bond people can feel to their environment, a bond with nature so often alienated in modern times by sprawling concrete and widespread urbanization. Working in the dirt alongside other creatures reminds us that we too are part of an ecosystem on which we rely.

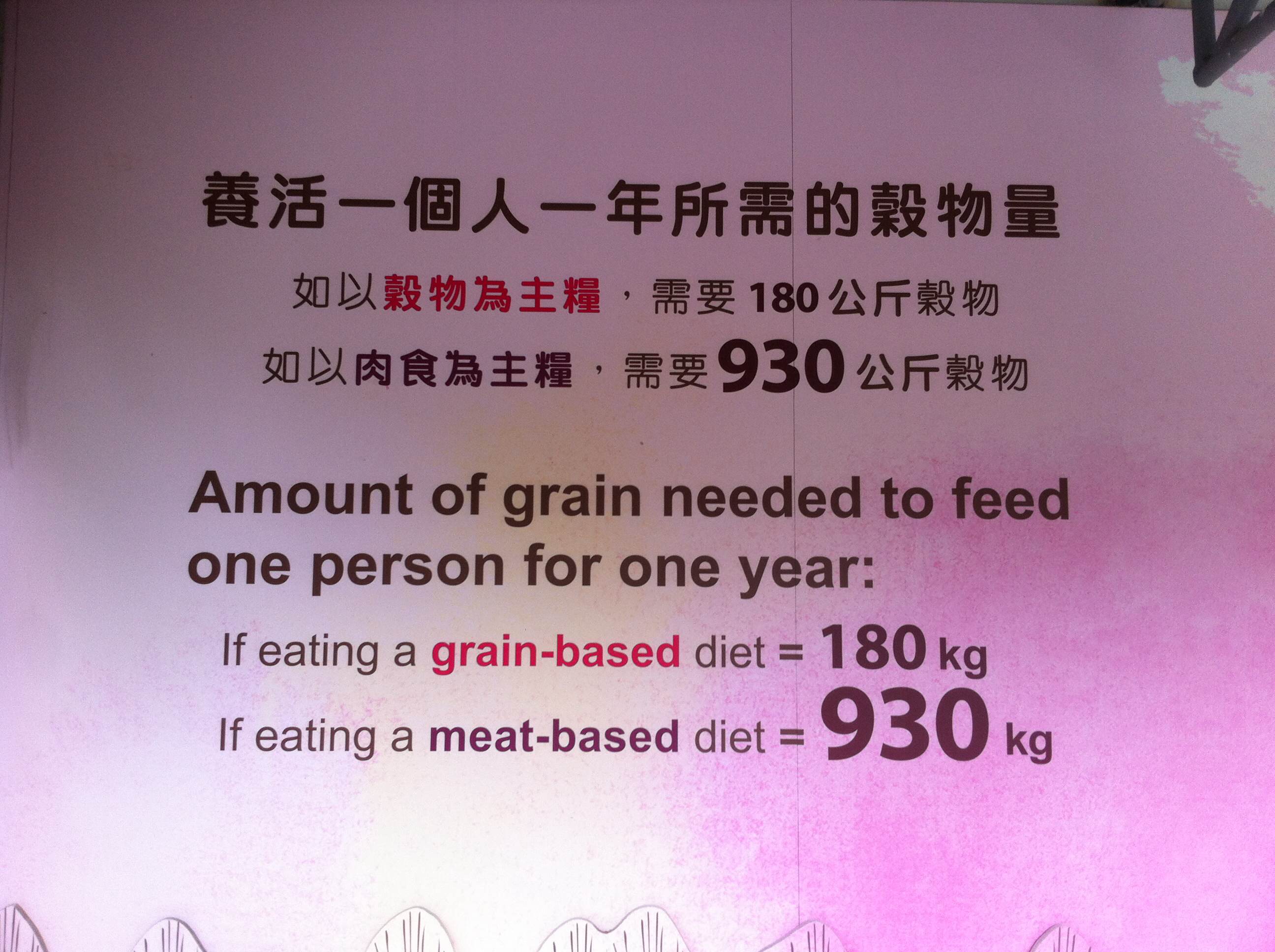

Vegetarian diets themselves help to reduce the energy we expend, and the current director of Kadoorie is a strong believer in this concept. His philosophy comes from a spiritual Buddhist belief in a respect for life. Materially a vegetarian diet cuts down on environmental degradation. In a 2009 study a Californian scientist found that a non-vegetarian diet consumed 2.9 times more water, 2.5 times more primary energy, 13 times more fertilizer, and 1.4 times more pesticide than a vegetarian diet (Marlow).

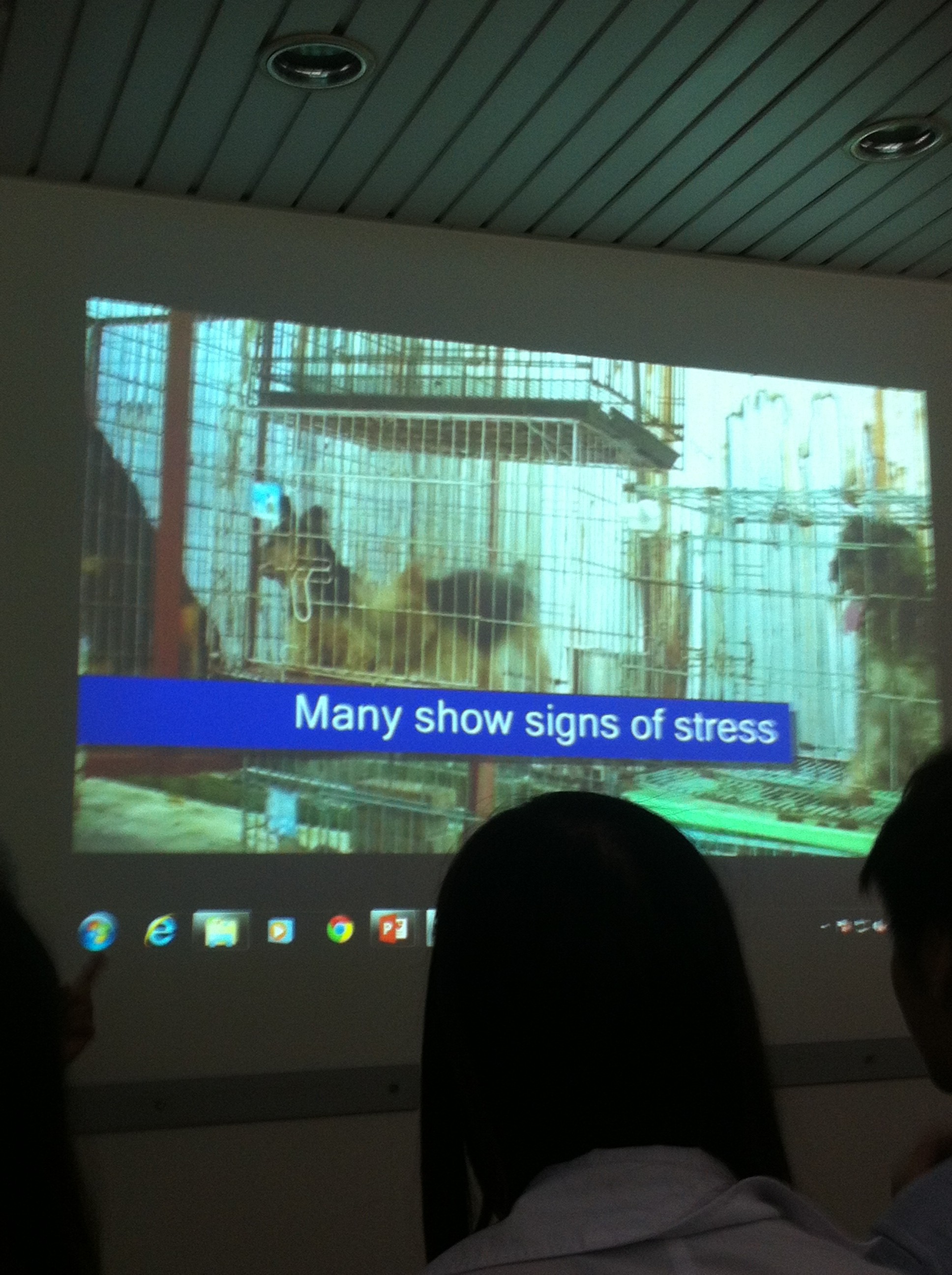

However, not all species are lucky enough to be omnivores who can choose where their sustenance comes from. For the carnivorous animals here at Kadoorie, meat is a must-have. The animals and insects used to feed the carnivores and insectivores, from chickens to the tiniest crickets are housed in spacious and well-kept enclosures and given a quality of life unimaginable to the factory farmed animals consumed by many people. The chicken playground (made of recycled kindergarten climbers), the large stick-bug tanks complete with climbing trees (which are properly humidified and heated for their comfort and health), and the egg-carton colonies which house the crickets and cockroaches all serve as testament to the compassionate nature of the policies employed here, and to the dedication of the keepers who maintain them daily.

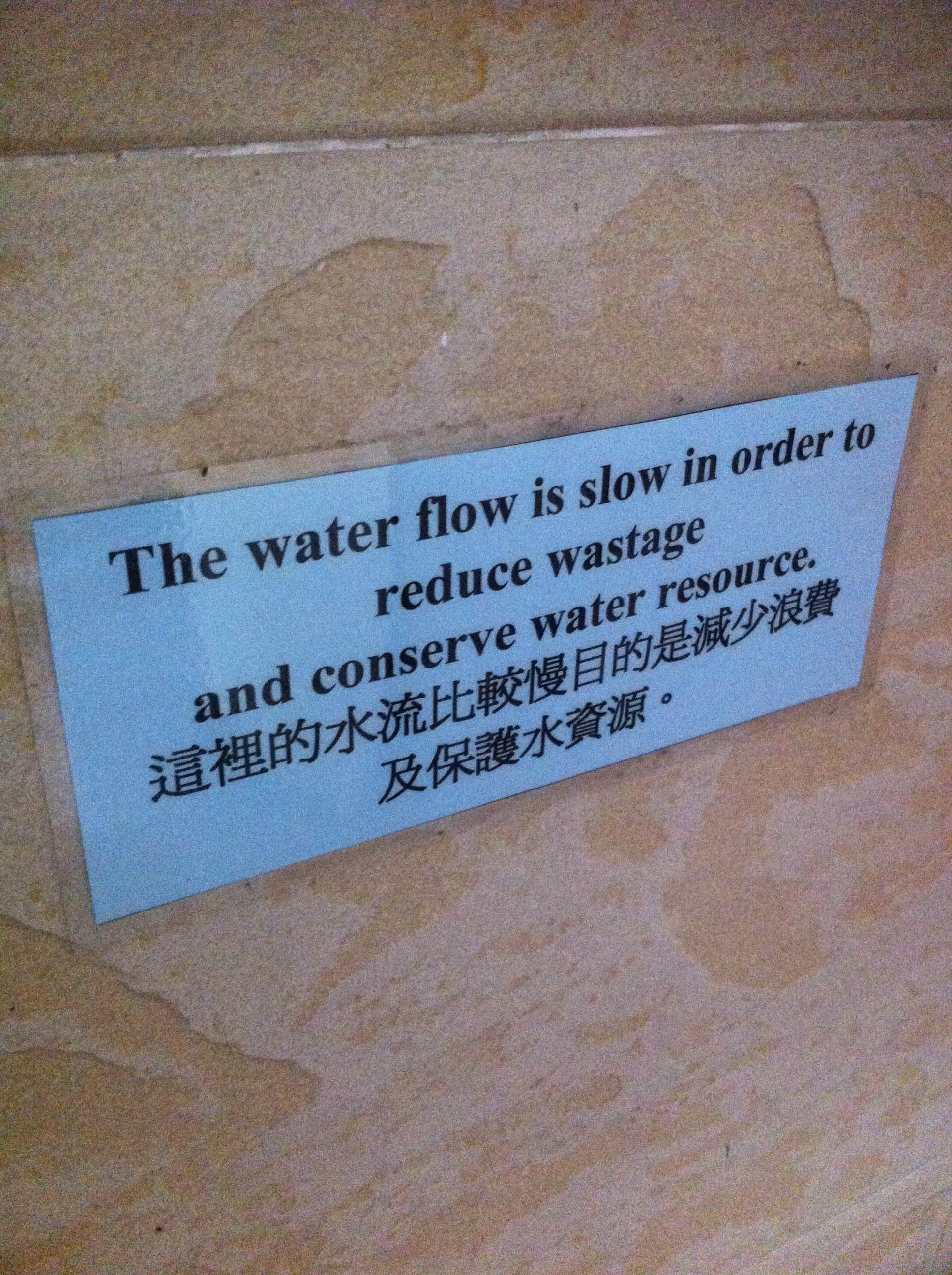

Even the water we drink here at Kadoorie has its own story. It comes from the beautiful stream that flows down Tai Mo Shan mountain. There are signs posted around the farm, in washrooms and kitchens, letting staff and visitors know the current status of the river, while reminding them not to use more water than they need.

A sign explains the low flow toilets – it is amazing how appliances and household items which are more environmentally friendly can add up over time.

Only certain taps are filtered drinking water, while the rest are unfiltered. When water is ‘purified’ it is safer for human consumption, but often changes the chemical balance of the water, which can have consequences on the delicate ecosystems and stream life – so keeping purification to a minimum is a great way to avoid indirectly affecting the wildlife. It is also wonderful because less filtered water means less chemicals and energy expended purifying water needlessly. Despite huge efforts to avoid needless energy consumption the vet tools, heating lamps, security alarms, and lights – not to mention the air conditioners – all still need power. To help offset some of the electricity used at Kadoorie there are solar panels on nearly every building around the farm which soak up energy all day from the sun.

The Goddess of Mercy, Kwun Yam, looks down from one of the peaks over Kadoorie Farm and Botanical Garden. She is a figure which embodies compassion for all things.

All of these things that Kadoorie Botanical Farms and Gardens does to be sustainable, they do while also rescuing, rehabilitating and caring for animals at the same time as they are also often engaged in complex multi-team research projects. It can get pretty intense around here but if they can do it – so can we!

Tasha and Karlie