Get a sense of where are going to spend June 2014…the rainy season!

Get a sense of where are going to spend June 2014…the rainy season!

My last week at Kadoorie ended where I began the placement, in the LED (Live Educational Displays). In the beginning I only had a few days in LED but over this last week I was able to gain much more insight into what many of the keepers have to do on a daily basis. It became very apparent that the relationship the people have with the animals is quite different from those in the WARC (Wild Animal Rescue Centre), and perhaps for obvious reasons. In WARC the animals arrive in a crisis, are cared for very closely; and the hope for them is that they will be rehabilitated and returned to the wild.  Caring for animals in WARC requires a level of focused attention as well as emotional distance. We don’t always know what’s going to happen to these animals. Often they come in injured or simply too young to survive and many do succumb. This bat was just days old and while he made it through the first night with feeding every hour or so, he didn’t make it through the second.

Caring for animals in WARC requires a level of focused attention as well as emotional distance. We don’t always know what’s going to happen to these animals. Often they come in injured or simply too young to survive and many do succumb. This bat was just days old and while he made it through the first night with feeding every hour or so, he didn’t make it through the second.  In the best of cases, they get released. Either way, the attachment of the carer can get in the way of making good welfare decisions for the sake of the animals. A certain kind of caring detachment allows for the focus to stay on the animals and their needs. Too much attachment, in some cases, can blind the carer to the best welfare for the animal.

In the best of cases, they get released. Either way, the attachment of the carer can get in the way of making good welfare decisions for the sake of the animals. A certain kind of caring detachment allows for the focus to stay on the animals and their needs. Too much attachment, in some cases, can blind the carer to the best welfare for the animal.

However, in LED the relationship between carers and animals is very different as these animals are long term residents. Because these animals are not facing either immanent death (the worst case scenario in WARC) or future release (the best case scenario) attachment is more acceptable, and perhaps even more important to the ongoing health and wellbeing of the animals. Many keepers in LED have emphasized that their closeness with the animals has a positive impact on the level of care they receive. The relationship becomes very intimate as each keeper is assigned to care for the same animals daily. Attachment to the animals allows for more tolerance for the animals at their worst. For example, the monkeys can be very difficult to handle as there are certain orders in which eating and transferring must occur. The monkeys always resist this order so it takes quite a while to succeed at whatever task is at hand. Having a close, intimate relationship with them allows for a greater ability to be patient with them, just as it does with loved ones in human families.

In each department different levels of care are required. The complex relationship between attachment and detachment have been a constant source of debate since we arrived. Both, it turns out, are advantageous but in different scenarios. In WARC, attachment is required at a level that allows for sufficient care of animals who are often in urgent need of support but not to the degree that the big picture surrounding the animal’s welfare is compromised as a consequence of what turns out to be what the humans need rather than the animals. In WARC a kind of attentive and concerned detachment seems to work best if the priority is to focus on the animal’s best interest. In LED where the circumstances are different, a certain level of attachment ends up being the basis for the best care for the animals. Like people, these animals have personalities which can be frustrating at times. If the keepers were not attached, if they didn’t already care, it would be easy to allow these frustrations to unintentionally impact the level and consistency of care that the animals receive. In the end, the issue of whether or not one should be emotionally attached or detached when caring for animals, comes down to the context in which we encounter the animals.

Krista Bouwman

For most of the Western world, the morning starts with a cup of coffee and people do love their brands: Tim Horton’s, Starbucks, McCafe, Pacific Coffee – the list goes on. But as many now know, the conditions of coffee production across the world are profoundly complicated. A handful of developing nations utterly depend on coffee as a primary export i.e., one of the few means by which they can participate in the global economy. So to meet the demand for export dollars as well as the ever increasing appetites of consumers, huge swaths of forest are being turned into plantations. And this doesn’t even touch on the issue of labour exploitation on those very same plantations! Coffee is nothing if not an ethical minefield – hence the burgeoning market for ‘Fair Trade’. But if the human and environmental costs of coffee weren’t enough of an ethical minefield, a newish trendy coffee is being flagged as unethical for a wholly different reason – cruelty to animals.

Kopi luwak is a type of Indonesian coffee that was popularized in Hong Kong in 2007 after its appearance in the movie starring Morgan Freeman and Jack Nicholson, “The Bucket List”. Due to its portrayal as a milestone life experience like seeing The Great Wall of China, or swimming the Great Barrier Reef corporations hopped on the bandwagon transforming this small locally consumed coffee into an intensive factory farmed global initiative. Kopi Luwak was marketed as exotic and prestigious, and became sought after by consumers. The coffee is made by harvesting the undigested coffee beans from the faeces of the masked palm civet, based on the belief that the animal will select only the finest examples of coffee beans, and that these will produce the best coffee. Though this is fairly unusual, removing the coffee beans from stool collected in the forest from wild civet would cause about as much harm as a nature hike. However, because of the time and energy that would be needed to find and collect the scat, the coffee made from it became extremely expensive and sought after boasting an export price as high as $230 per pound (TIME Magazine, November 25th 2012). Ironically the scarcity and price helped to create a demand and once that was in place quantity became more important than the supposed quality. The end result of this is that civets were poached, caged, and force fed nothing but a diet of coffee beans until they were too ill to continue digesting them, and were dumped back into the wild where their weakened state would often result in them dying (SPCA Hong Kong, Pawprint Magazine, Issue 93, Feb. 2014). A diet of only coffee leads to chronic malnutrition as well as illness resulting from the high caffeine intake.

Of the consumers of Kopi Luwak coffee, many would be unaware of the way it’s made. Of those who do know, some are likely to be apathetic regarding the implications for the animal but some might actually be outraged or disgusted enough to stop drinking it. As is so often the case with prestigious brands, however, a few would find the image cultivated by the drink or simply their own enjoyment of it to be worth the exploitation and suffering that went into it. Sometimes, in what seems to be a vague acknowledgement of the true conditions in which it’s produced, the coffee is labeled as ‘harvested from the wild’, but the BBC as well as the animal rights activist group PETA both did research which found that these labels were often fraudulent (BBC, “Civet cat coffee’s animal cruelty secrets”) (PETA, “Help Civets Suffering from Cruel Coffee”).

The SPCA in Hong Kong has pushed public awareness about the ethical issues surrounding Kopi Luwak. Public support due to increased awareness thanks to these efforts and the efforts of other groups has caused Kopi Luwak to be taken off the menu at many expensive cafes and five star hotels, although overall it is still readily available. To further inform consumers, studies in America have shown that in a blind test, people overwhelmingly do not find Kopi Luwak preferable to other coffees. This case study shows how the media can portray an item to play on the desires and emotions of its consumers while never telling the whole story. In the instance of Kopi Luwak, ideas about luxury, prestige, and having the finest things in life have driven the market despite the reality that the product itself is indistinguishable from many other coffees. Given this reality what possible justification can there be for the ongoing suffering of the civets?

A quick Google search will reveal the conditions of factory farms. Go ahead – try it. Search “conditions of cattle on factory farms” or “chicken pens on factory farms” or “battery hens”. The conditions and methods of slaughter will vary from country to country but these cattle, sheep, pigs, chicken, goats, rabbits, emus, and other animals are typically suffering every bit as much as the civets. The meat in North America is usually packaged in neat little styrofoam containers and by the time it is purchased, its resemblance to an actual animal is virtually non existent. Many North Americans would be outraged or nauseated by the sight of whole animal carcasses or the live animals that are the staple of wet markets, such as the ones here in Hong Kong. The truth is though, there is a very good chance that the animals seen in these places suffered less than the cows those sterile cuts of beef at the supermarket came from. The consumer never has to see the suffering that is caused to the animals in order to obtain so many of our staple food products, and this separation allows many people to go on buying things which facilitate the cruel treatment of animals and the degradation of the environment. And our so called ‘animal protection’ laws allow this. It’s called ‘necessary suffering’ when it’s agricultural animals we are talking about and it’s only unnecessary suffering our animal protection laws address.

This photo dated 07 December 2002 shows a civet sitting inside a cage at a market in Guangzhou, in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong.

Because many people really do care about animals, they flock to free range, organic, or certified free trade labels, believing that these labels really do indicate a better quality of life and death for the animals that are the source of these products. But it turns out this is far from the truth. So called ‘compassionate consumer’ labeling practices are often misleading at best, and downright false at worst. For instance ‘free run’ eggs aren’t happy chickens wandering around in fields. On the contrary they are massive barns jam packed with hens all of whom have still had their beaks burned off soon after hatching and all of whom are living in their own putrid fetid waste a lot of the time.

It is hard to condemn consumers for relying on labelling. The time and effort to get beneath the labelling is beyond the scope of many people. So, while labels which give consumers a simple way to make ethical choices might be a step in the right direction, it primarily just gives people a sense of relief from the guilt they feel from knowing the truth about the treatment of livestock and the planet in a global economy which cares more about profit than the conditions of production. Too often sadly, corporations do the bare minimum to put these ‘ethical’ labels on their products, not for the sake of the animals, but to make them more appealing. They have no genuine concern for the animal or the environment, but instead use these often psuedo-ethical labels to increase their prices and gouge consumers who are just trying to do the right thing. It seems nearly impossible to navigate the aisles of a grocery store when so many ‘ethical’ labels and ingredient lists hide more than they reveal. And marketing itself is a whole issue in itself, between the false promises, the appeals to our emotions and desires, and the hidden cruelty, it is hard to feel that we aren’t being tricked constantly by corporations. But we, as consumers do bear some responsibility, especially in the age of the internet where all manner of information about the truth of factory farming is available at a keystroke. Our willingness and our ability to alienate ourselves from the conditions of production allows a variety of unethical practices to continue unimpeded by concerned consumers. Willpower, in combination with access to the truth are important elements to support an ethic that means people have to refuse otherwise desirable things – such as delicious food or prestigious coffee – and when the ethical issues are hidden or blurred by labels with false promises and ritzy beautiful coffee shops it becomes all too easy to just not consider them at all.

It is interesting to see how public pressure has had many successes in limiting the production of Kopi Luwak and convincing people not to buy it while animal cruelty in factory farms remains endemic, despite the overwhelming environmental and ethical reasons to change. There may be some obvious reasons for this – Kopi Luwak is a fad, while the consumption of meat is so deeply embedded human cultures in so many complex ways. Meat consumption is deeply caught up in how we see ourselves as a species and how we relate to others. In a complex interplay of identity politics supported by notions like tradition and power meat eating is inseparable from ideas of class, gender and even ethnicity. Put simply, those who can dominate others eat meat – the rich eat meat because they can afford it but the poor cannot; men eat meat because it is manly to be ‘king of the grill’ and to hunt and kill. Meat eating is one of the buttresses for western notions of cultural superiority. Westerners eat meat and thrive while the rest of the world and especially the developing world, subsists rather than thrive’s on a diet of grains and vegetables. This has more to do with ideology than anything about necessity. And on top of the complex constructions of meat as desirable, it also tastes good and is sold as a rich source of nutrition. In the end, pleasure seems to be the primary reason for the ever increasing consumption of meat in the world today but the question remains, is human pleasure enough to justify the wholesale suffering of billions of animals let alone the environmental degradation that arises as a consequence of satisfying our voracious appetites. It’s good to remember that “worldwide meat production (beef, chicken and pork) emits more atmospheric greenhouse gasses than do all forms of global transportation and industrial processes.” (Nathan Fiala, citing the US Food and Agriculture Organization, Scientific American, Feb 2009, Vol 300, Issue 2, p72-75).

Tasha and Karlie

During my stay with the SPCA I had the opportunity to visit Tung Choi Street with Shuping Ho (a researcher at the SPCA) and four SPCA interns, all studying law at Hong Kong University (Jacqueline Ma, Michelle Cheng, Jane Li and Shirley Choi) . Tung Choi, also known as Goldfish Street, is famous for the sheer number of shops selling all sorts of animals from local species to exotics, but mostly fish and reptiles. These shops waste no space when it comes to the display of their animals. They are often in small overcrowded tanks and not provided with the proper housing conditions (such as heat and UV lights for reptiles), and many of them are even sick. It is a stark contrast to what pet shops are like in Canada, for the most part. While most of the stores were selling fish and reptiles there were nonetheless plenty of puppies, kittens, rabbits and hamsters also available. Almost all the pups and kittens were high end, very expensive breeds; no mutts in these stores. While the animals were being kept in clean and reasonably spacious cages out front, our suspicions were that out the back of the stores was another story. It was easy to hear barking from behind the closed doors where customers were not allowed to go. Another suspicious feature of all the pet stores was the ‘no photo’ signs everywhere.

During our time at the SPCA we learned that the reality of the origins of those designer pups and kittens in the pet stores is an unregulated puppy and kitten mill industry where animals are kept in shockingly poor conditions. Much of the SPCA’s investigation work is directed towards finding these mills and shutting them down, while their lobbying work is directed towards encouraging the government to regulate breeders. The pictures below depict the real conditions behind the scenes of the Tung Choi pet shops. The SPCA website has lots of information on the pet industry and especially the puppy trade. Please visit this link for more information on the Boycott the Bad Breeder Campaign http://boycottbadbreeder.com. For information on the upcoming legislative reforms around breeders, see http://www.spca.org.hk/en/outreach/campaigns/spca-hk-urges-for-cap-139b-amendment

Goldfish Street, as the name suggests, is really known for the phenomenal array of fish shops. Many species of fish are put into bags and hung on display on wire racks, often in the baking sun. Not only do the fish end up overheating in water too hot for them, they also run out of oxygen.

This pushes the fish into extremes and ultimately causes their death as they cannot survive either the low oxygen levels, nor rapid temperature changes. At night, once the shops close, the bags are simply cut open and dumped into the street, including the dead or near dead fish.  To the store owners, the dead fish don’t even put a dent into their pockets as they cost so little in the first place and are sold at a much higher market value. Even if they only manage to sell a few fish and lose considerably more, they are still profiting. While the display practices might be different in Canada – ie we’re not baking fish in the sun in plastic bags, the idea of disposability at the heart of breeding them in vast numbers is the same.

To the store owners, the dead fish don’t even put a dent into their pockets as they cost so little in the first place and are sold at a much higher market value. Even if they only manage to sell a few fish and lose considerably more, they are still profiting. While the display practices might be different in Canada – ie we’re not baking fish in the sun in plastic bags, the idea of disposability at the heart of breeding them in vast numbers is the same.

For example, I used to breed fish and would sell some to pet stores. They would purchase the fish from me at $3 apiece and then turn around and sell them for $12.99 apiece. For them, there is a 430% price increase so with those economies of scale, we can see how individual fish lives become irrelevant in the big scheme of things where profit margins mean more.

From Tung Choi Street our tour of the pet shop trade took a slight detour. While snakes are kept as pets in Hong Kong, just as they are in Canada, they are also eaten. So our HKU law intern friends led the way as we went off in search of the snake soup shops.  Eating snakes is part of traditional Chinese medicine, more specifically it’s a Cantonese delicacy and it supposedly has high nutritional value. Snake eating is a practice more common in the winter and it seems to be decreasing in popularity with the generations. Young people are less inclined to follow this tradition and in fact none of the HKU interns had ever tried it. The soup typically contains two species of snake, and they could just as well be deadly, along with spices. At the stores we visited, one had ball pythons on display, and the other had cobras. The snakes are kept live in drawers, like the ones in the photo below, until you want to order the soup and are thus killed and prepared fresh.

Eating snakes is part of traditional Chinese medicine, more specifically it’s a Cantonese delicacy and it supposedly has high nutritional value. Snake eating is a practice more common in the winter and it seems to be decreasing in popularity with the generations. Young people are less inclined to follow this tradition and in fact none of the HKU interns had ever tried it. The soup typically contains two species of snake, and they could just as well be deadly, along with spices. At the stores we visited, one had ball pythons on display, and the other had cobras. The snakes are kept live in drawers, like the ones in the photo below, until you want to order the soup and are thus killed and prepared fresh.

Turns out, snake soup shops don’t just offer snakes, they also sell steamed crocodile and turtle soup! While eating turtle jelly – a derivative of the plastron of turtle shells, is fairly common in Asia, the experience of actually eating turtle soup was as new to the interns as it was to us. But we found ourselves in one of those situations where the hospitality of the shopkeeper who welcomed us in to look at the snakes, also put us in the position where we needed to return the favour. When she offered turtle soup – we were in a jam. So the compromise was one bowl and 6 spoons! This was one of those moments where I wish I was vegetarian!  None of us liked it, but the pressure was too great to refuse. Thankfully, Shuping was a champ and finished off the soup for us.

None of us liked it, but the pressure was too great to refuse. Thankfully, Shuping was a champ and finished off the soup for us.

After that experience we went to a local café to rid the taste of the soup! Bring on the Hong Kong version of high tea!

One of the most surprising things about the day was learning that, at least on the face of it, the stores weren’t breaking the law, whether they were selling exotic, Cites listed animals – as many of them were – or not (Cites is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and is the reference point for regulating the trade in endangered animals). All the pet stores needed to be lawful was to be licensed by the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department and as long as the animal can sit down, stand up, turn around and lay down the enclosures then they comply with the existing standards of care required by the animal protections laws. Even the turtles kept in the tiny tanks filled with water were considered ok, because they met the above requirement. So while it seems the pet stores at least comply with certain laws, questions remain about the industry overall. Puppy mills, for example, are also an enormous problem in North America, with Quebec in Canada having the dubious reputation of being the puppy mill capital of the continent. So while pet stores in Canada may not be the primary way puppies and kittens are making it to market, the same problem of designer dogs bred in awful welfare conditions for a seemingly insatiable market applies. And like HK, Canadian animal shelters are full of the very same dogs and cats who later get abandoned or surrendered or dumped – along with their mutt cousins! So whether it’s Cites listed endangered animals whose commercial sale gets around the law because they were supposedly bred in captivity, or puppy mill kittens and puppies whose lives begin in appalling conditions, or goldfish whose lives as individuals simply don’t register as a welfare concern, the gaping holes in the regulation approach to animal welfare seem really apparent. Without the means to implement even the existing regulations, these laws are unable to offer much to the animals who are their subjects.

Zack

In the Fauna conservation Department at Kadoorie there are many tasks that must be undertaken to maintain the smooth operation of the facility. One vital task is the training of the different animals that are part of the long term animal facility – the LED (Live Education Display). For some of the larger animals in LED such as: the boars, crocodiles, raptors and monkeys training is an important part of the daily routine. Without the training of these wild animals the daily activities that keep them safe and healthy would be neither efficient or safe for both the keepers and the animals.

Boars: The boars are trained to lift their feet as well as to go in and out of transportation crates. Both of these actions are necessary as each is done to check the health of the animal. Their legs must be lifted in a controlled manner in order to properly check the underside of their hooves, as they are prone to infections. Quite often the boars must be weighed and again, it is important that this happen in a controlled environment. The boars have been trained via food rewards to become familiar with the transportation crates that are used to weigh them. Wild boars can be very aggressive; they could easily and inadvertently threaten the life of the people who are providing the health care they need just by virtue of their size and their tusks. The hoof lifting and crate training protects the health and safety of both person and boars.

Crocodiles: For some of the crocodilians here at the farm there is quite an unusual trick used in order for the keepers to enter the enclosure. The keepers have trained the crocodiles, when they hear music (Fleur De Lys no less!), to exit their outdoor enclosure and move into an indoor contained area with a door. When the crocs are inside the keepers are able to enter and clean. Obviously this is a learned behaviour but unlike animals trained for human entertainment – this isn’t a trick. It’s a necessary behaviour that is directed towards enhancing the crocodile’s welfare. It’s good animal centred husbandry. For the crocodile, the alternative would be enduring the daily stress of being captured and re-located, simply in order to clean their home. Clearly, providing an opportunity for the animal to move by itself is an animal centred way of accomplishing the same end. For the keepers this is a more efficient, safer and humane way of providing the crocs with their essential needs in a captive environment.

Raptors: Many of the raptors are undergoing falconry training; this means that they are being trained to come down to the person when beckoned. Again, this is a stress preventative for the raptors and a safety measure for the keeper. This training has another important role as well, which involves education of the public. If the public is able to interact with these winged beasts up close and personal, the hope is that it will inspire a love and appreciation of them and further the possibility of cultivating a conservation ethic – especially in the children. In this regard, Kadoorie’s LED follows the same principle as many zoos. The hope here is that greater exposure to animals will produce greater compassion.

Monkey: As discussed in a previous post, there is a very specific order to moving the monkeys around. This goes for transferring them from cage to cage and eating in front of one another. The keepers have trained them to come, sit and stay on their perches. This is necessary because when feeding and transferring cages, the dominant monkeys must go last. Normally, they would go first, however, in this scenario the other monkeys would be too scared to follow. This is the same for feeding; they are currently training the older monkeys to be nicer to Sita (see post #??) during feeding by rewarding them with peanuts when they allow Sita to eat near them. This may seem like it isn’t all that important but it allows the keepers to work safely and effectively with the monkeys. It also encourages positive behaviour between the monkeys and their mates. We have seen the monkeys’ behaviour with the training and they are difficult at best. Without the training it would be near impossible to manage these creatures and keep them happy with each other. Of all the animals at Kadoorie, the monkeys are perhaps the hardest to manage and this is precisely because they have the most complex social structures. Captive environments, let alone ones based on rescue principles, dramatically alter the wild social structures of these primate colonies and so they create stresses and tensions that wouldn’t emerge in the wild. In captivity the goal is to keep everyone alive and relatively content. In the wild, a monkey like Sita probably wouldn’t survive. She would simply be rejected and die.

In previous posts we have spoken of the person-animal relationship and how forcing animals to suppress their instinctive behaviours can affects them negatively. Vast numbers of animals are held in captivity globally in a variety of contexts – from exotic pet ownership to back yard zoos to the city zoos that are part of the human lives of most nations. The Live Educational Displays department at Kadoorie has shown us some of the real world challenges of keeping wild animals in captivity when the focus is on their health and wellbeing rather than human entertainment. Training in this context is essential to everyone’s safety, yet can look a little like teaching animals to do tricks. Though it can be argued that it isn’t right to alter an animal’s so called natural behaviour, when in captivity, the most efficient and least stressful circumstances must be the focus. If an animal’s only option is captivity, these ‘tricks’ become an essential aspect of their wellbeing.

Although, training animals to perform tasks is a common activity found in recreational attractions parks like Canada’s Marineland and Hong Kong’s Ocean Park, the animal training done at Kadoorie can clearly be distinguished by considering the goal. The point here, as noted throughout this post, is different. The point of the training here at Kadoorie – is animal centred, not human centred. Theme parks train their animals for the sole purpose of human entertainment and if there is an interest in the animals health and wellbeing, it’s generally an economic one. Keeping performance animals healthy is good business. At Kadoorie, however, the training of the animals is done for the very important intention of enhancing the well being of the animal without compromising the safety of the people who care for them.

It is fascinating to consider the way the issue – the animal that is trained to do a trick – means something very different in different contexts. When the focus is on animal welfare and not on human entertainment, the trained behaviour is just that, trained behaviour. But the very same behaviour in a theme park is indeed a trick and not one that enhances the life of the animal. On the contrary the trick is for us.

Running a rescue centre and a number of live educational displays takes a lot of effort, small but invaluable daily tasks of proper animal husbandry, and (among other things) resources. From feed for the animals to energy to run the entire facility, the cogs and gears that keep an organization this big running are often overlooked, but critically important. After working at the Kadoorie Farm for a few weeks, we began to wonder where it all came from, so we did some investigating.

Both animals, staff and visitors are fed primarily with produce and product grown on the farm. Both the Sun Garden Cafe and The Farm Shop offer a wonderful selection of vegetables, grains, and eggs which are either locally grown or harvested from the farm itself, as well as various fertilizers for people’s own backyard gardens or farms.

The agricultural part of the farm still grows crops, and there is also an eco-garden to teach visitors about growing their own food, along with a employee garden so staff can grow their own food and grab a snack on the go.

In addition to this, the Cafe uses no disposable utensils, napkins, or take-away containers. Both of these small, but important strategies decrease the damage caused to the environment by the use of fossil fuels in transportation. The lack of disposable cutlery cuts down on the amount of garbage produced, as well as waste which can cause harm to animals who consume it, and would increase the space needed for huge dump sites – further destroying animal (and human) habitats. There is very little recycling in Hong Kong, and the places who do accept recyclable waste have to ship it all the way to mainland China to be processed. The landfills here are overflowing (as is true of most heavily populated areas in the world), but instead of managing waste with recycling programs, and green bins for organic waste Hong Kong has recently licensed an incinerator in Tuen Mun. This quick fix will have huge impacts on both local citizens and the environment by raising the regional temperature by 1-2 degrees Celsius and increasing fume emissions detrimentally leading to more greenhouse gasses and higher risk of lung cancer in humans and animals (Terry Li Kwai Fong).

In the abstract, eating and growing food locally strengthens the bond people can feel to their environment, a bond with nature so often alienated in modern times by sprawling concrete and widespread urbanization. Working in the dirt alongside other creatures reminds us that we too are part of an ecosystem on which we rely.

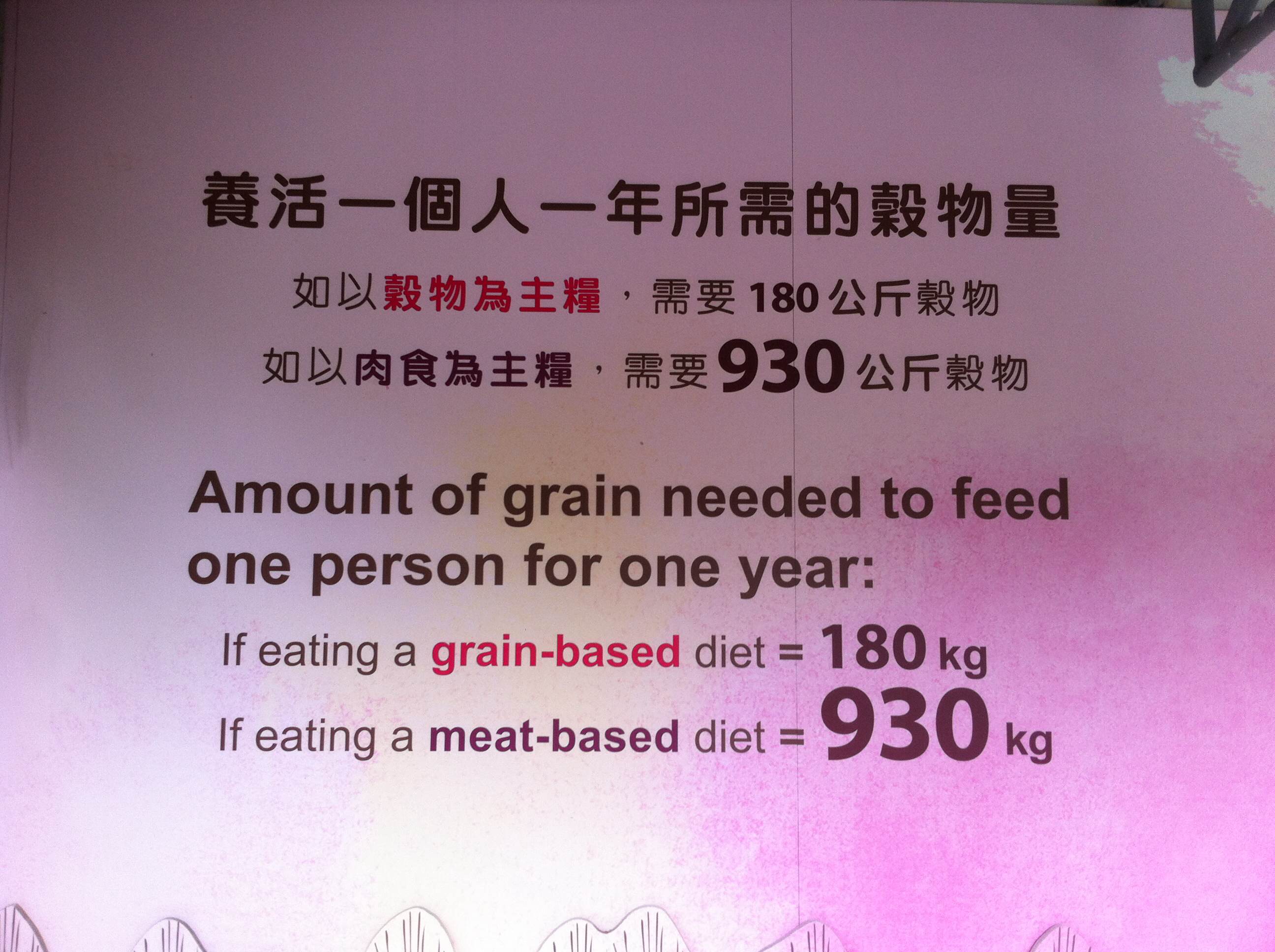

Vegetarian diets themselves help to reduce the energy we expend, and the current director of Kadoorie is a strong believer in this concept. His philosophy comes from a spiritual Buddhist belief in a respect for life. Materially a vegetarian diet cuts down on environmental degradation. In a 2009 study a Californian scientist found that a non-vegetarian diet consumed 2.9 times more water, 2.5 times more primary energy, 13 times more fertilizer, and 1.4 times more pesticide than a vegetarian diet (Marlow).

However, not all species are lucky enough to be omnivores who can choose where their sustenance comes from. For the carnivorous animals here at Kadoorie, meat is a must-have. The animals and insects used to feed the carnivores and insectivores, from chickens to the tiniest crickets are housed in spacious and well-kept enclosures and given a quality of life unimaginable to the factory farmed animals consumed by many people. The chicken playground (made of recycled kindergarten climbers), the large stick-bug tanks complete with climbing trees (which are properly humidified and heated for their comfort and health), and the egg-carton colonies which house the crickets and cockroaches all serve as testament to the compassionate nature of the policies employed here, and to the dedication of the keepers who maintain them daily.

Even the water we drink here at Kadoorie has its own story. It comes from the beautiful stream that flows down Tai Mo Shan mountain. There are signs posted around the farm, in washrooms and kitchens, letting staff and visitors know the current status of the river, while reminding them not to use more water than they need.

A sign explains the low flow toilets – it is amazing how appliances and household items which are more environmentally friendly can add up over time.

Only certain taps are filtered drinking water, while the rest are unfiltered. When water is ‘purified’ it is safer for human consumption, but often changes the chemical balance of the water, which can have consequences on the delicate ecosystems and stream life – so keeping purification to a minimum is a great way to avoid indirectly affecting the wildlife. It is also wonderful because less filtered water means less chemicals and energy expended purifying water needlessly. Despite huge efforts to avoid needless energy consumption the vet tools, heating lamps, security alarms, and lights – not to mention the air conditioners – all still need power. To help offset some of the electricity used at Kadoorie there are solar panels on nearly every building around the farm which soak up energy all day from the sun.

The Goddess of Mercy, Kwun Yam, looks down from one of the peaks over Kadoorie Farm and Botanical Garden. She is a figure which embodies compassion for all things.

All of these things that Kadoorie Botanical Farms and Gardens does to be sustainable, they do while also rescuing, rehabilitating and caring for animals at the same time as they are also often engaged in complex multi-team research projects. It can get pretty intense around here but if they can do it – so can we!

Tasha and Karlie

The pig nose river turtle, an animal that is indigenous to Northern Australia and South Western New Guinea, is listed as a vulnerable species under the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List (http://www.iucnredlist.org). Unlike any other species of freshwater turtle, the pig nose is extraordinary in having flippers resembling marine turtles. According to the IUCN, the term ‘vulnerable’ is defined as “a taxon which is facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future” (IUCN 2001).

KFBG received a shipment of 785 pig nose turtles from the government as a result of an illegal import in 2009. They were being smuggled into the country for the pet trade and the clock started ticking immediately on the fate of these hatchlings. At a mere 10 cm, the turtles required a lot of care as they were originally shipped in such poor conditions. Many had died as a result of stress and malnourishment but during the eight months that it took the governments of Indonesian West Papua and Hong Kong to work together to determine what would happen to them, the staff of Kadoorie managed to save 609 of the original shipment. But the biggest question facing all the stakeholders who were involved in the turtles’ long term fate was determining for certain where they had come from in the first place. Releasing animals back into the wild is a very complicated process, something we will detail more at the end of this post. Fortunately for these particular turtles, there was paper evidence from shipping which helped determine that the turtles were in fact from Indonesian West Papua.

A decision was made to release the turtles back into the wild, however the logistics of such a task are considerable. Custom shipping boxes had to be built, and the turtles could only be in the boxes for a limited time. On top of that, a constant and specific temperature also had to be maintained as well as fresh water supplied, but not too much or they could drown. KFBG felt it was important to do a trial run with 8 turtles to see if they could survive the trip before sending them all. These are but a few of the issues faced with the return and release of these animals. Eventually, however, various hurdles were jumped and the turtles were released in October 2011 in the Maro River in Indonesian Papua. This was an all too rare repatriation success story for KFBG and the various governments. The complexities of returning to the wild animals seized from the illegal pet trade is more often than not stalled by insurmountable barriers around international and national laws, which compound the more obvious problem of just working out where they came from.

Thanks to the extraordinary efforts of the KFBG teams the villagers in the Maro River were educated about sustainability and the importance of preserving the turtles, thereby minimizing the risk to the potential of this population from human poaching and fishing. But pig nosed turtles take up to 15 years to reach full reproductive maturation and the average survival rate to that point of many wild turtle species is often not much more than 1%. When released these turtles were still juveniles, thus their capacity to repopulate the region would not be achieved, or even measurable for nearly 15 years. So this is obviously a very long term research challenge. While 609 turtles were released the reality is that it is likely that only a very small percent will survive to adulthood. Tracking the survival rate data of the pig nosed turtles was left in the hands of the villagers who, along with two other communities along the Maro, had pledged to protect them and to provide the local Forestry Officers with updates if sightings occurred. Given the remoteness of the Maro community this was perhaps the most resource rational way of trying to ensure some longer term data could be made available but anecdotal evidence is the weakest level of evidence, often yielding fairly unreliable results. So the repatriation of the turtles raises some critical conservation questions. If we don’t fund the research to reliably assess long term survival of returned species can we really claim anything much more than provision success?

Taking a different angle on the question of success though, the repatriation of the pig nosed turtles was a worldwide success from a number of different points of view. Kadoorie was able to identify where the smuggled species originated, which, given the illegal nature of smuggling is very rare. Compounding the typical suppression of shipping details is the fact that there is often insufficient data summited to GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), the open access DNA databank that is a vital resource to tracing the exact provenance of particular animal species. So after locating the area where the pig nosed turtles could be released attempts to create a grassroots movement within the community surrounding the river were initiated. This was a large part of the turtle’s release success because such communities are likely to also be the poachers who sell the turtles to the trade involving animal trafficking in the first place. Educating them and providing them with viable economic alternatives were central aspects of even the provisional success of this wildlife restoration attempt.

Interestingly, the particular approach to education in Maro was extensively focused on educating the youth of the nearby tribes to value the importance of conservation in terms of local wildlife preservation. Once again, this is a long term investment that works on the assumption that changing the hearts and minds of the children is the equivalent of investing in the leaders of the future. But in Maro it was also the case that the Chief was very instrumental in the success of the release and in educating the rest of the villagers. So he was a key player in managing the immediate issue of preserving the turtles while educating the children on sustainability managed the future. The turtle restoration wouldn’t have taken place without extensive collaboration from numerous stakeholders in addition to the folks at KFBG including the Hong Kong and Indonesian governments, various other conservation NGO’s, even the commercial airlines who helped with transport costs of the turtles and of course the villagers of Bupul. Investing in these collaboration not only advances global conservation efforts they help to raise global consciousness about the potential to preserve and even save critically endangered species.

As noted above, as far as releasing animals back into the wild goes, it is a very long and complicated process. One cannot simply release an animal anywhere as it may not be native to that region. Increasingly scientists are revealing the importance of micro-environments to the particularity of certain species. Releasing animals of a separate sub-species could alter the gene pool of the existing population negatively, and the animals might find themselves in ecosystems that cannot sustain them. There are a number of potentially negative impacts to be considered very carefully before any decisions can be made regarding the release of animals which have crossed international borders. GenBank is a critical resource for this kind of aspiration. It allows DNA to be matched with DNA of animals in other areas and can offer information on where the animals originate. However, this system currently has its limitations because it relies on scientists voluntarily submitting samples. While the database is growing all the time the task of logging all the DNA of all species in all regions of the globe is an insurmountable one. And in the case of the pig nose turtle it wasn’t GenBank that provided the provenance of the turtles in the end, it was a combination of reasoned logic and paperwork. It was highly unlikely the turtles were smuggled from Northern Australia. The Australian Navy is constantly patrolling those waters for illegal human smuggling so it’s unlikely that the turtle smugglers would risk an encounter with the Australian military. It was therefore more logical to look towards West Papua as the origin of the turtles and sure enough on this rare occasion the shipping documents had enough information to actually support this hypothesis. Through collaboration with International Animal Rescue Indonesia, the Wildlife Conservation Society and the ministry of Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia a suitable release site was determined near Bupul, in the Maro river. Had there been a DNA profile of these and similar turtles in GenBank, however, a release site may have been found much faster. As it happened, the pig nosed turtles were released into a river where once pig noses had thrived but where they had not been seen for over 20 years. The gamble was that the river system could still support them.

Given how important DNA is to the possibility of returning to the wild animals that have been seized for the illegal food and pet trade, the DNA database is a critical resource. Yet how plausible is it to begin DNA testing animal populations around the world, including those in remote areas for conservation efforts? What would the resource implications of such an effort be and is it the best use of conservation resources at this time? What would the cost of such a mass project be? GenBank is an attempt to do just this but the fact that it’s voluntary has implications on how comprehensive and therefore how useful it can be. It’s like the wiki of genetic material but hasn’t yet taken off in quite the same way. Even if we could conceivably accomplish a complete biodiversity DNA map, we are in a period of mass species loss right now. And then there’s the question of evolution and the fact that genes change over time. Perhaps that makes the task easier – for all the wrong reasons – but another question emerges anyway. How useful can a DNA bank be in the face of gene flow and genetic drift? These are just some of the complex questions raised by even a successful conservation effort like the project to return the pig nosed turtles to the wild.

Zack and Jacqueline

This week was our first week at the SPCA. We were paired up with inspectors, who go out on a daily basis answering to emergency rescue calls. The hotline gets information about various animals in need. On our first day, we rescued a cat from a wet market (fresh meat and produce markets) where it had been in one of the stores for four days without food or water. We also rescued an exotic bird, a dog that had been hit by a car and two more cats that had found themselves in sticky situations.

What we’ve gathered from our very brief experience with the inspectors so far is that there are some fascinating differences between Canada and Hong Kong when it comes to animals and people. Many of the animals that we would think of in Canada as pets, especially the street dogs, are often as afraid of the people as the people are of them. This makes the work of helping them when they are sick or injured that much more difficult. While walking to the SPCA on Monday we tried to give a street dog some water, which it clearly needed, but its fear overwhelmed its need to drink and it ran away. Perhaps the difference lies in part in the fact that Canada doesn’t have such a visible stray animal problem, which is not to say it doesn’t have a problem – just that it’s not as visible. But it’s also true that in Hong Kong different dogs are socialized to have different relationships with humans. There are the true pets who are very used to humans, the community or loosely owned dogs who are often a bit more circumspect and the truly feral dogs who won’t come near humans voluntarily (http://www.spca.org.hk/en/animal-birth-control/community-dog-programme). The category we don’t tend to have in Canada are the loosely owned or community dogs.

Despite the different categories of dogs, some things are the same. Today we went to try to capture a semi-feral, feral or perhaps even loosely owned dog – it’s not always easy to tell the difference – that has an enormous tumour protruding out of its stomach. If and when this dog is caught it will likely be euthanized a: because it is suffering and b: because it will need surgery and medication and the costs would be prohibitive for an animal that even if it survived, would likely not be adoptable. The same welfare based approach would probably happen in Canada. What compounds this dog’s circumstances in Hong Kong, however, is not only its status but its size. Given the space restrictions in Hong Kong, the public is a lot less likely to adopt a large dog to begin with, let alone one that might need considerable medical care. While the idea of euthanizing an animal simply because it needs expensive medical attention raises complex moral questions the same dilemma emerges in Canada on a daily basis. Such intensive veterinary care is often prohibitively expensive and many simply cannot afford it. This economic barrier to good welfare pushes people towards abandonment, surrender to shelters or euthanasia.

But it is also true that in Canada the overall culture, including economics, surrounding companion animals has shifted considerably around veterinary care and people are increasingly encouraged to go to extreme lengths to provide their pets with medical intervention at all costs – literally! Surgeries running to the thousands of dollars are not unusual. But this raises the question of the relationship between class/economics and welfare. It’s only those people with money who can genuinely afford to provide this kind of care for their animals and this is as true in Hong Kong as it is in Canada. For those who don’t have access to the same financial resources the options are fewer – go into debt to pay the bill, abandon, or surrender the animal. Against this backdrop then, prolonging the life of an animal like the one with the tumour, seems like a poor use of very limited resources. For a street dog, there are few options.

In conclusion, there are interesting similarities as well as differences emerging especially around the challenge and management of unwanted animals. In both countries, paradoxically, euthanasia is often the option that is seen to be in the best interests of the animal; this is the animal welfare focused option.Yet ‘welfare’ is clearly inseparable from economics.

Krista and Ryanne

The gang at the SPCA with the paw prints, and shell prints of some of the adoptees. From right to left: Karlie, Krista, Jacqueline, and Tasha

Today the group woke up bright and early to meet Shuping Ho, our SPCA host, at the bus stop; she works as a Researcher in the department of animal welfare at the SPCA. After a ride on the 64K bus into Kowloon and a quick trip on a very crowded peak hour metro to Tsim Sha Tsui we got on the Star Ferry to cross the harbor. From there we could see the SPCA front and centre on the waterfront.

In Canada 56% of all households have at least one cat or dog, while some people also keep small birds, rodents, reptiles, or fish (Perrin 48). The identity of these animals varies according to the preferences of their owner/human companion – they are considered to be everything on a scale from simple unintelligent creatures, to intelligent workers, friends, and some of us even consider them our kin. In Hong Kong the culture of pet keeping is relatively new. Things are different in Hong Kong. According to Tony Ho, Chief Officer of the SPCA Inspectorate, only about 10% of Hong Kong households have a cat or dog. A misconception we had before arriving in Hong Kong was that many people were afraid of large dogs or domestic animals because of a lack of exposure to them growing up, and while this may in part be true, clearly the tide is turning. Many people, especially in the urban areas of Hong Kong island itself and Kowloon, seem to like dogs and cats, but cannot keep them due to an array of barriers: public housing doesn’t allow dogs and many private landlords don’t want to rent to people with dogs either. And then there are the very significant limitations of space to compound the situation. Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated areas in the world with the island itself having a population density of 6,290 people per square kilometre. Put in perspective, Toronto has a population density of 945.4 people per square kilometre! The whole of Hong Kong, meaning Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories – where we are – covers a total of 1,104 square kilometres with a population of over 7 million. The Greater Toronto Area is 7,125 kilometres with the same population. Perhaps it’s not so surprising that people in Hong Kong don’t have a big culture of pet keeping! There’s very little space, most people live in high rises, rents are astronomical – some of the highest in the world – and people work very long hours here.

The laws surrounding animals are very different here. The main two laws which protect animal welfare are Cap169, The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance and Cap169a, The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulations which date back to 1935 when Hong Kong was still under the rule of the British (Hong Kong Department of Justice). By contrast animal protection/welfare in Canada is administered by a complex web of federal, provincial and municipal laws and there can be considerable variation across jurisdictions regarding what is and is not addressed in the legislation. In Ontario, for example, animal welfare laws were first enacted through the Ontario SPCA Act in 1919 and had not been significantly updated until fairly recently when Ontario introduced the Provincial Animal Welfare Act which became law in March 2009. The new Act created new standards of care (Provincial Animal Welfare Act, 50-c.16) and significantly upgraded the potential offences including a new section on causing or allowing distress to animals as well as causing harm to law enforcement animals.

Animal welfare regulations in Hong Kong apply to both domestic pets and animals sold as live food in wet markets, which causes distortions in how pets are allowed to be treated. What would be humane for an animal who only needs to be kept short-term until they are sold and killed for food may not be appropriate when applied to a pet being kept in the long-term. As the law applies to all animals without exception, however, these regulations can be detrimental to the well-being of pets. One such rule states that an animal need only be kept in a cage big enough to stand up and turn around. The SPCA recognizes that these rules are outdated and has continuously advocated to improve these laws and update them to more ethical policies. In some parts of Ontario including Toronto, the number of domestic animals allowed in one home is six (Toronto Municipal Code 349-5). In Hong Kong there is no legal limit to the number of animals a person can keep, once again a rule remaining from when the animals were primarily used as food. One consequence of this is that the lack of a legal restriction means they don’t have the option to charge people for having a huge number of animals, for example, people who run illegal puppy mills. But even in Canada, where we do have legislation like this, it differs province by province. Thus we can have Quebec colloquially known as the’ puppy mill capital’ of North America, because its laws are so lax, the fines for being caught so low, and prosecution, not exactly a high priority for police.

The standard of animal welfare enforced by the law is lower than in Canada and Britain, but many people here in Hong Kong still have strong personal beliefs about the safety, protection, and overall welfare of domestic animals. For instance during our orientation we talked about the SPCA’s standard of welfare. Here they operate on the principle of “The Five Freedoms” – a standard commonly used to determine whether an animal is being humanely kept which encompasses: freedom from hunger and thirst, freedom from distress and fear, freedom from illness and disease, freedom to show normal behaviours, freedom from discomfort. These standards, although not enshrined in the law, are used by the SPCA to educate tens of thousands of children about pets every year, and to give advice to pet owners who may not be taking optimal care of their animals.

The SPCA works paw-to-paw with the police, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, as well as Kadoorie Farm and Botanical Gardens. Although the SPCA does receive government funding, relative to other sources it is very small, about 1%. As with most NGOs that also have a watch dog role to play around legislative reform, a fine balance has to be struck between maintaining institutional autonomy and fostering good working relations with all stakeholders, including government, the public and even sometimes other activists.

Another way the SPCA works to protect animals and foster a climate where there are fewer conflicts with humans is through the Animal Population Management program an example of which is the Trap-Neuter-Release program which has been very successful in managing the stray cat population in Hong Kong. Alongside this initiative of the SPCA the government and the quasi government administered Ocean Park are engaged in managing the feral dog and monkey populations which continually come into conflict with people. Complicated questions continue to arise around management strategies and even entitlement as humans increasingly encroach on what has been the animals’ territory. It is true that domestic pets should be neutered and spayed in order to prevent litters that cannot be cared for, but the feral dogs and cats of Hong Kong are as wild as the monkeys in many cases, and have shared the land with the humans since they were first taken in or displaced by them. This raises questions of the ethics of human settlement and population. As it currently stands, however, TNR programs save the lives of thousands of animals each year.

Despite their exemplary work, intensive training programs, and genuine dedication, the SPCA here, like the SPCA and Humane Societies in Canada, can sometimes find themselves to be the target of the media. Just as news broadcasts in North America tend to be sensationalized and polarized in order to enthrall viewers by serving more as entertainment than as balanced information, the Hong Kong media has also been guilty of the same thing. Polarizing representations, especially of euthanasia, garner considerable public attention but they rarely offer an insight into the complex process that actually goes into making each individual decision, let alone the systemic forces that make euthanasia a necessary option in the first place. But in the spirit of ‘any press is good press’, perhaps even the polarizing representations of animal welfare may have a silver lining if they can be used as an opportunity for greater public awareness and education. And education is clearly a high priority for the Hong Kong SPCA and one of the aspects of their work which is focused on pro-actively preventing the problem rather than reactively responding to it. The more people can be educated to take responsibility for neutering and caring for their animals the fewer animal welfare issues there will be. This is especially true of the ‘loosely owned ones’ – these are particularly the dogs who often guard buildings and businesses who tend not to registered, microchipped, collared or neutered but who do have owners, at least right up until the authorities appear at their doorsteps. When that happens, they conveniently become ‘street dogs’ – not owned by anyone. So while sensationalism is a complex issue and can (and often does) lead to more detrimental outcomes for animals as well as reductive and demeaning portrayals of serious and informed animal activists, there may be an aspect of this type of media which serves an educational end in raising public awareness. This can be compared, for instance, to the unlawfully obtained farming and slaughterhouse videos done by PETA, which resulted simultaneously in a zealous oversimplification of issues of animal welfare, especially in the factory farming industry, at the same time as it fuelled the already vicious backlash culture working against animal rights activism. Nonetheless, it did break through the usual cone of silence on animal welfare issues. A mixed blessing perhaps.

-Karlie & Tasha

Works Cited

Hong Kong Department of Justice. Bilingual Laws Information System. Chapter 169.a-b (The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance)

Perrin, Terri. The Business of Urban Animals Survey: The Facts and Statistics on Companion Animals in Canada. Can Vet. January 2009: 50(1): 48-52 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2603652/

Provincial Animal Welfare Act, 2000, chapter 16 – Bill 50 (amended)

TORONTO MUNICIPAL CODE CHAPTER 349, ANIMALS – Article III (349-5. Number of cats and dogs restricted)

Our group, Krista and Ryanne, worked in the live educational display (LED) section this week at Kadoorie Farm and Botanic gardens. This means that we worked with a zoo keeper helping her with her daily tasks. Of all the animals we encountered during the day our favourite was the Macaques. This is a type of monkey that lives in the area and like many primates they are very social creatures. In the wild, they live in troops.

Our group, Krista and Ryanne, worked in the live educational display (LED) section this week at Kadoorie Farm and Botanic gardens. This means that we worked with a zoo keeper helping her with her daily tasks. Of all the animals we encountered during the day our favourite was the Macaques. This is a type of monkey that lives in the area and like many primates they are very social creatures. In the wild, they live in troops.

At Kadoorie, there are 7 Macaques: Rambo, Rosie, Darlexi, Sita, Oliver, Woowoo, and Quasi. These monkeys are of varying age and have found themselves to be at Kadoorie for a variety of reasons. For some of the younger monkeys, like Sita and Oliver, their mother was no longer capable of caring for them. For many of the other monkeys the government picked had them up as they were causing a public disturbance. For example, Woowoo was caught many times causing a ruckus at the hospital finding food by scavenging through the garbage.

In Hong Kong there is the urban area and then there is nature; there is not much of an in-between state. With Macaques there is great competition for food, especially in the winter. Any monkey that becomes ostracized struggles to survive. These are the conditions when they most often begin to stumble upon human garbage and find that this is able to satisfy their hunger. Eventually, they make the connection that humans equal food; which in turn results in the harassment of humans by the monkeys. And make no mistake cute turns to kind of scary pretty quickly: these monkeys can be quite aggressive so they become a nuisance to humans.

The human-animal relationship is a complex one. In this scenario, despite being so closely related to humans, the monkeys are often not seen as being sentient and intelligent like us. Instead, once they come into conflict with humans, they are more clearly positioned on the animal side of that boundary. Yet people often lay the foundation for this conflict by encouraging the monkeys by feeding them. And when relations break down the government gets called to deal with the “problem”. The immediate solution to the problem can result in captivity and sometimes euthanasia, an outcome that is less than ideal for anyone and one that doesn’t tackle the root of the problem.

The human-animal relationship is a complex one. In this scenario, despite being so closely related to humans, the monkeys are often not seen as being sentient and intelligent like us. Instead, once they come into conflict with humans, they are more clearly positioned on the animal side of that boundary. Yet people often lay the foundation for this conflict by encouraging the monkeys by feeding them. And when relations break down the government gets called to deal with the “problem”. The immediate solution to the problem can result in captivity and sometimes euthanasia, an outcome that is less than ideal for anyone and one that doesn’t tackle the root of the problem.

Once in captivity, it becomes very hard to provide these creatures with the stimulation they need. At Kadoorie there is a divide between the monkeys. The older monkeys (Rosie, Rambo and Darlexi), do not get along with the younger monkeys (Sita, Quasi, Woowoo and Oliver). Despite the best efforts of Kadoorie staff only half of them get to go outside for the day (though the mini-troops are rotated regularly). Captivity cannot provide the kind of space, nor relationships that simulate the wild and the artificial structuring of troops is often not all that successful.

In addition to the monkeys’ not getting along, the way they came to be here in the first place plays a role in their future ability to be accepted by members of their own species. For example, Sita was hand raised by people as she came to Kadoorie at only two weeks old. Understandably, she prefers the company of humans rather than her fellow Macaques and one unintended consequence of saving her life is that she has to manage being bullied by the other monkeys. This is a perpetual dilemma that is constantly being negotiated in rescue work with animals.

In addition to the monkeys’ not getting along, the way they came to be here in the first place plays a role in their future ability to be accepted by members of their own species. For example, Sita was hand raised by people as she came to Kadoorie at only two weeks old. Understandably, she prefers the company of humans rather than her fellow Macaques and one unintended consequence of saving her life is that she has to manage being bullied by the other monkeys. This is a perpetual dilemma that is constantly being negotiated in rescue work with animals.

An interesting question that arose for us concerned the question of animal identity. When you take away an instinctual part of an animal`s life (such as living with and choosing their own troop), do you take away the identity of these animals? In other words, is Sita only part Macaques? It is easy to see that she has a need for humans yet for her own sake she lives with monkeys. But it’s an uneasy ‘living’. Sita doesn’t fully understand group dynamics nor does she altogether seem to enjoy interactions with her own kind. She would be shunned in the wild and she is being shunned in captivity. It is a wicked problem – a dilemma that arises in part because we are damned if we do – i.e. if we save them, and we are damned if we don’t. Whatever we do, it won’t be the wild, but will it be wild enough? Most of the time, if Kadoorie is an example of what we can do, the answer is yes, it is enough – but only with an enormous amount of commitment, care and resources.

Ryanne and Krista

On Wednesday, Jacqueline and I worked in the Live Educational Display at Kadoorie. We were matched with one of the zookeepers to assist him in his daily routine for the morning. His area includes both the mammals and the reptiles. The morning work consisted of cleaning the enclosures and providing the animals with fresh water, checking animal behavior, counting all of the bats, scattering food in the animal enclosures to encourage foraging, and assisting with the wild boars. We worked specifically with fruit bats, barking deer (that’s me, Zack, and the barking deer below), several turtle and tortoise species, Chinese water dragons, wild boar, water monitors, a masked palm civet and leopard cats.

Animals can arrive at Kadoorie multiple ways. Most of them are injured or rescue animals from the wild. Some come from illegal imports via the government until a court case is settled and the government decides the fate of the animals. Other animals (primarily snakes) are brought in by the police because they were in close proximity to humans who they want them removed. A few even come in as abandoned exotic pets. Depending on the time of the year, the number and species of animals that arrive at Kadoorie changes. For example, only in the winter for a timeframe of two months, there is a species of bird that ends up at Kadoorie due to its migration path as the birds often run into the skyscrapers in Hong Kong. Due to such a variety of ways animals arrive at the center, the work is hectic and constantly unpredictable. Kadoorie frequently receives confiscated shipments from the exotic animal trade and once received a shipment of what ended up being 7 000 turtles. They then must care for and maintain the turtles until the government and various other often international stakeholders, decides what to do with them. This process can sometimes take years, as multiple governments become involved since these imports usually pass through a series of countries on their way into China. Futhermore, the courts might have cases they deem more important and therefore put off the animal case until they deal with the other cases. This raises interesting questions about the status of animal in relation to the law. Kadoorie, however, sometimes has to turn down animals. This is done primarily because they either do not have the housing available, the animal has no conservational value or they know there is no positive outcome so the animals will end up euthanized.

While helping the keeper with his daily tasks we got a sense of how much work it is to maintain even the few animals that are kept at Kadoorie for educational purposes. Just the two wild boars alone, which are a part of their Live Animal Educational Display, take an enormous amount of time and work. The daily process of maintaining them includes cleaning the pen area, feeding the animal and providing care for their specific needs. For example, treating their hooves and providing mental stimulation are essential to their long term health. These tasks might seem simple but they require a lot of forward planning because of the risk involved while interacting with what remains a wild animal. The occupation of simply caring for the boars’ hooves now involves training the wild animal to perform certain helpful tricks so that the keepers can have access to their feet. This is done through positive reinforcement training involving food. The wild boars have learned, much like domesticated horses, to raise their foot, bow and to walk forward and backwards. These are exercises that the boars would not need to perform in the wild but are essential to their ongoing health in captivity. Because these boars are wild animals certain complications arise that would not normally be an issue in their native environment. The two male boars – brothers – unexpectedly had to be separated after many years of living peacefully together due to the aggressive and dominant tendencies that arose after separating them for a brief period for processing. Once reintroduced the conflicts occurred where before there were none. Due to their new behaviours the boars are now separated for the sake of the keepers’ safety and their own. This is a problem that the boars would not have faced in the wild because they would have had enough space to ‘work it out’. The enclosure Kadoorie provides, while luxurious by many standards, is not big enough to support such antics, so a simple fence has been put in place to keep the boys apart. That combined with hormone therapy makes for a more harmonious existence. The story of the boars is the tip of the iceberg of the complexities involved with maintaining the physical and mental health of wild animals in captivity.

Zack and Jacqueline