The gang at the SPCA with the paw prints, and shell prints of some of the adoptees. From right to left: Karlie, Krista, Jacqueline, and Tasha

Today the group woke up bright and early to meet Shuping Ho, our SPCA host, at the bus stop; she works as a Researcher in the department of animal welfare at the SPCA. After a ride on the 64K bus into Kowloon and a quick trip on a very crowded peak hour metro to Tsim Sha Tsui we got on the Star Ferry to cross the harbor. From there we could see the SPCA front and centre on the waterfront.

In Canada 56% of all households have at least one cat or dog, while some people also keep small birds, rodents, reptiles, or fish (Perrin 48). The identity of these animals varies according to the preferences of their owner/human companion – they are considered to be everything on a scale from simple unintelligent creatures, to intelligent workers, friends, and some of us even consider them our kin. In Hong Kong the culture of pet keeping is relatively new. Things are different in Hong Kong. According to Tony Ho, Chief Officer of the SPCA Inspectorate, only about 10% of Hong Kong households have a cat or dog. A misconception we had before arriving in Hong Kong was that many people were afraid of large dogs or domestic animals because of a lack of exposure to them growing up, and while this may in part be true, clearly the tide is turning. Many people, especially in the urban areas of Hong Kong island itself and Kowloon, seem to like dogs and cats, but cannot keep them due to an array of barriers: public housing doesn’t allow dogs and many private landlords don’t want to rent to people with dogs either. And then there are the very significant limitations of space to compound the situation. Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated areas in the world with the island itself having a population density of 6,290 people per square kilometre. Put in perspective, Toronto has a population density of 945.4 people per square kilometre! The whole of Hong Kong, meaning Hong Kong Island, Kowloon and the New Territories – where we are – covers a total of 1,104 square kilometres with a population of over 7 million. The Greater Toronto Area is 7,125 kilometres with the same population. Perhaps it’s not so surprising that people in Hong Kong don’t have a big culture of pet keeping! There’s very little space, most people live in high rises, rents are astronomical – some of the highest in the world – and people work very long hours here.

The laws surrounding animals are very different here. The main two laws which protect animal welfare are Cap169, The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance and Cap169a, The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulations which date back to 1935 when Hong Kong was still under the rule of the British (Hong Kong Department of Justice). By contrast animal protection/welfare in Canada is administered by a complex web of federal, provincial and municipal laws and there can be considerable variation across jurisdictions regarding what is and is not addressed in the legislation. In Ontario, for example, animal welfare laws were first enacted through the Ontario SPCA Act in 1919 and had not been significantly updated until fairly recently when Ontario introduced the Provincial Animal Welfare Act which became law in March 2009. The new Act created new standards of care (Provincial Animal Welfare Act, 50-c.16) and significantly upgraded the potential offences including a new section on causing or allowing distress to animals as well as causing harm to law enforcement animals.

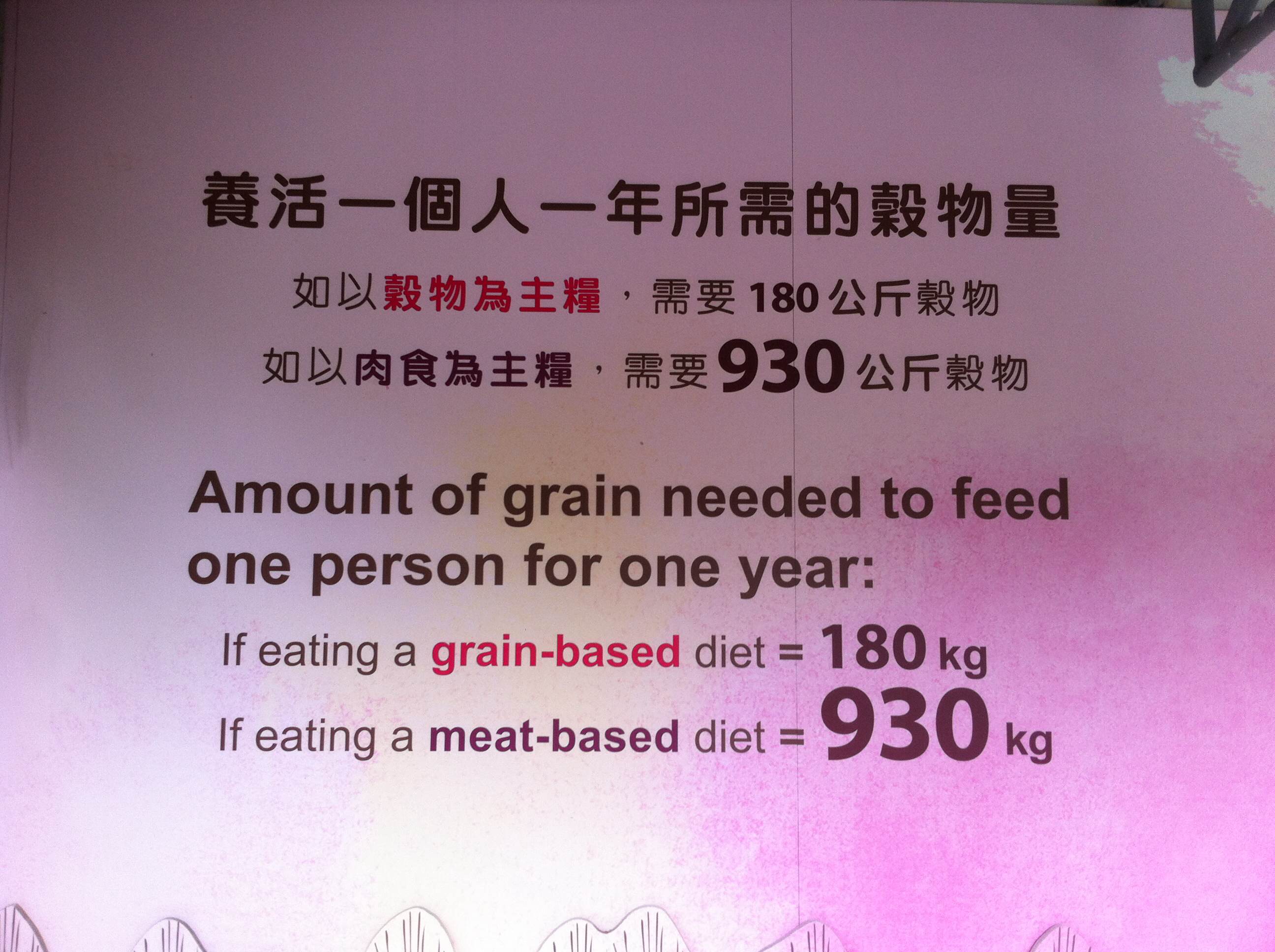

Animal welfare regulations in Hong Kong apply to both domestic pets and animals sold as live food in wet markets, which causes distortions in how pets are allowed to be treated. What would be humane for an animal who only needs to be kept short-term until they are sold and killed for food may not be appropriate when applied to a pet being kept in the long-term. As the law applies to all animals without exception, however, these regulations can be detrimental to the well-being of pets. One such rule states that an animal need only be kept in a cage big enough to stand up and turn around. The SPCA recognizes that these rules are outdated and has continuously advocated to improve these laws and update them to more ethical policies. In some parts of Ontario including Toronto, the number of domestic animals allowed in one home is six (Toronto Municipal Code 349-5). In Hong Kong there is no legal limit to the number of animals a person can keep, once again a rule remaining from when the animals were primarily used as food. One consequence of this is that the lack of a legal restriction means they don’t have the option to charge people for having a huge number of animals, for example, people who run illegal puppy mills. But even in Canada, where we do have legislation like this, it differs province by province. Thus we can have Quebec colloquially known as the’ puppy mill capital’ of North America, because its laws are so lax, the fines for being caught so low, and prosecution, not exactly a high priority for police.

The standard of animal welfare enforced by the law is lower than in Canada and Britain, but many people here in Hong Kong still have strong personal beliefs about the safety, protection, and overall welfare of domestic animals. For instance during our orientation we talked about the SPCA’s standard of welfare. Here they operate on the principle of “The Five Freedoms” – a standard commonly used to determine whether an animal is being humanely kept which encompasses: freedom from hunger and thirst, freedom from distress and fear, freedom from illness and disease, freedom to show normal behaviours, freedom from discomfort. These standards, although not enshrined in the law, are used by the SPCA to educate tens of thousands of children about pets every year, and to give advice to pet owners who may not be taking optimal care of their animals.

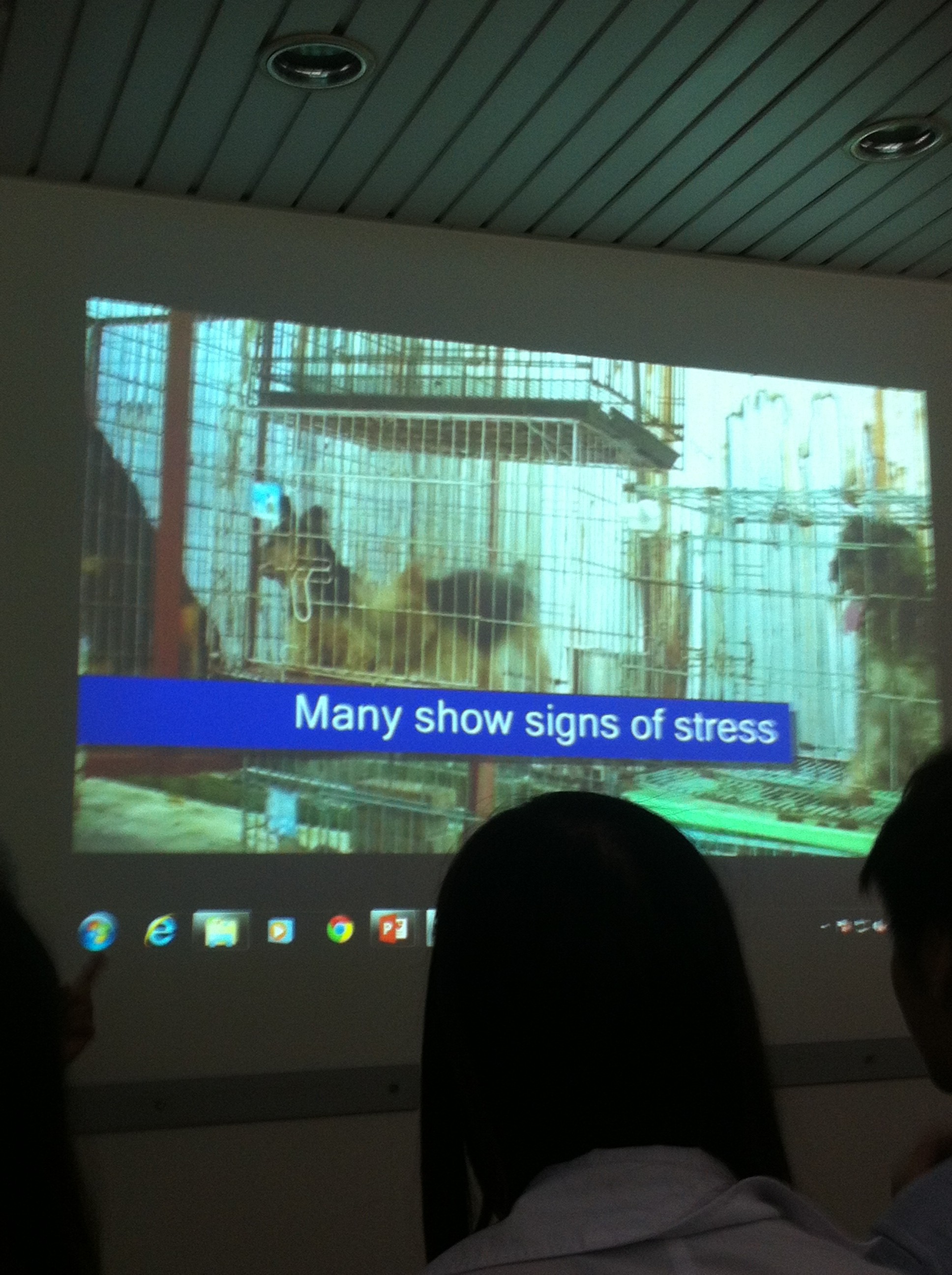

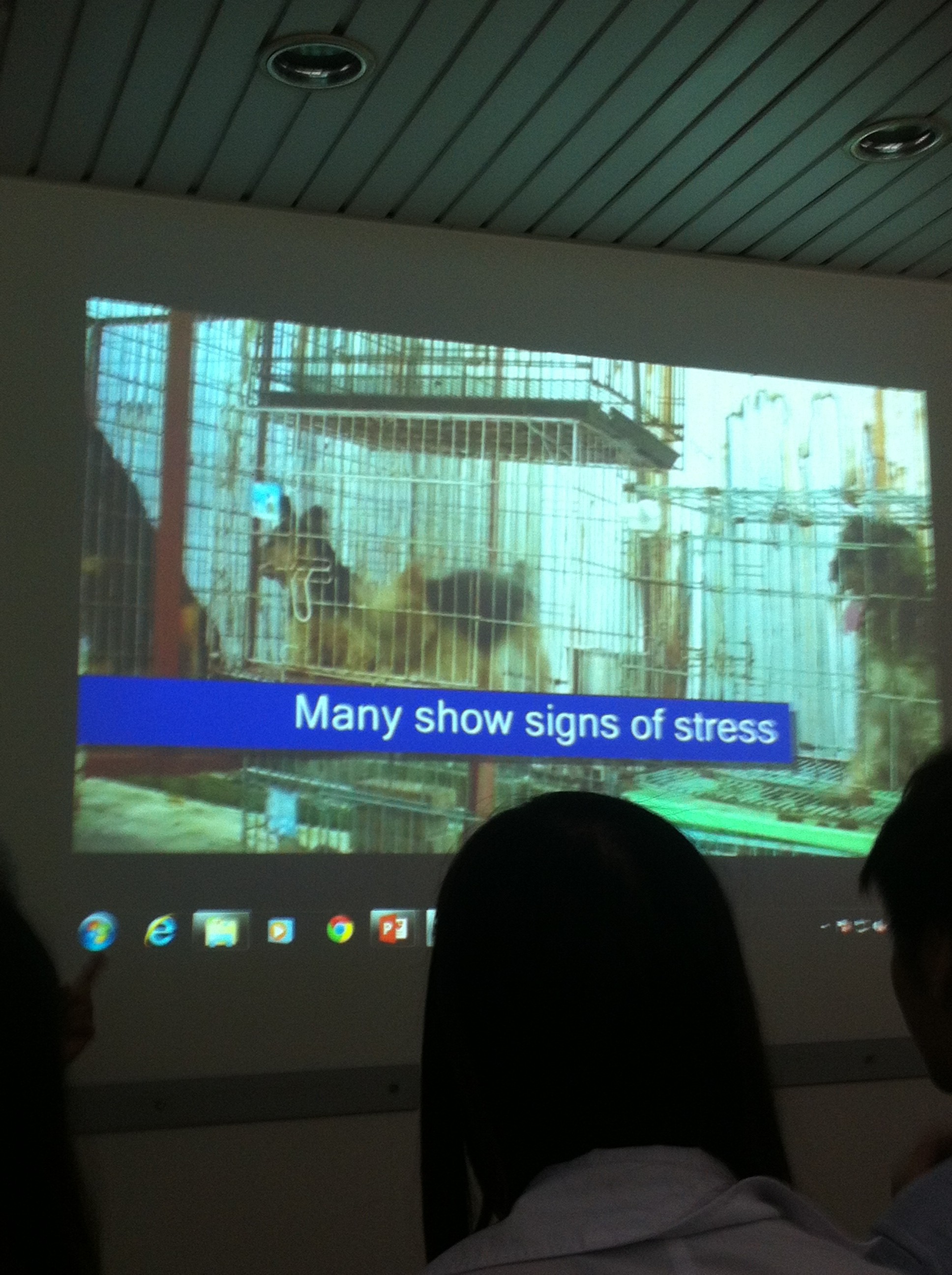

A slide from a case study about bad breeders and puppy mills.

The SPCA works paw-to-paw with the police, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, as well as Kadoorie Farm and Botanical Gardens. Although the SPCA does receive government funding, relative to other sources it is very small, about 1%. As with most NGOs that also have a watch dog role to play around legislative reform, a fine balance has to be struck between maintaining institutional autonomy and fostering good working relations with all stakeholders, including government, the public and even sometimes other activists.

Another way the SPCA works to protect animals and foster a climate where there are fewer conflicts with humans is through the Animal Population Management program an example of which is the Trap-Neuter-Release program which has been very successful in managing the stray cat population in Hong Kong. Alongside this initiative of the SPCA the government and the quasi government administered Ocean Park are engaged in managing the feral dog and monkey populations which continually come into conflict with people. Complicated questions continue to arise around management strategies and even entitlement as humans increasingly encroach on what has been the animals’ territory. It is true that domestic pets should be neutered and spayed in order to prevent litters that cannot be cared for, but the feral dogs and cats of Hong Kong are as wild as the monkeys in many cases, and have shared the land with the humans since they were first taken in or displaced by them. This raises questions of the ethics of human settlement and population. As it currently stands, however, TNR programs save the lives of thousands of animals each year.

Despite their exemplary work, intensive training programs, and genuine dedication, the SPCA here, like the SPCA and Humane Societies in Canada, can sometimes find themselves to be the target of the media. Just as news broadcasts in North America tend to be sensationalized and polarized in order to enthrall viewers by serving more as entertainment than as balanced information, the Hong Kong media has also been guilty of the same thing. Polarizing representations, especially of euthanasia, garner considerable public attention but they rarely offer an insight into the complex process that actually goes into making each individual decision, let alone the systemic forces that make euthanasia a necessary option in the first place. But in the spirit of ‘any press is good press’, perhaps even the polarizing representations of animal welfare may have a silver lining if they can be used as an opportunity for greater public awareness and education. And education is clearly a high priority for the Hong Kong SPCA and one of the aspects of their work which is focused on pro-actively preventing the problem rather than reactively responding to it. The more people can be educated to take responsibility for neutering and caring for their animals the fewer animal welfare issues there will be. This is especially true of the ‘loosely owned ones’ – these are particularly the dogs who often guard buildings and businesses who tend not to registered, microchipped, collared or neutered but who do have owners, at least right up until the authorities appear at their doorsteps. When that happens, they conveniently become ‘street dogs’ – not owned by anyone. So while sensationalism is a complex issue and can (and often does) lead to more detrimental outcomes for animals as well as reductive and demeaning portrayals of serious and informed animal activists, there may be an aspect of this type of media which serves an educational end in raising public awareness. This can be compared, for instance, to the unlawfully obtained farming and slaughterhouse videos done by PETA, which resulted simultaneously in a zealous oversimplification of issues of animal welfare, especially in the factory farming industry, at the same time as it fuelled the already vicious backlash culture working against animal rights activism. Nonetheless, it did break through the usual cone of silence on animal welfare issues. A mixed blessing perhaps.

-Karlie & Tasha

Works Cited

Hong Kong Department of Justice. Bilingual Laws Information System. Chapter 169.a-b (The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance)

Perrin, Terri. The Business of Urban Animals Survey: The Facts and Statistics on Companion Animals in Canada. Can Vet. January 2009: 50(1): 48-52 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2603652/

Provincial Animal Welfare Act, 2000, chapter 16 – Bill 50 (amended)

TORONTO MUNICIPAL CODE CHAPTER 349, ANIMALS – Article III (349-5. Number of cats and dogs restricted)

Caring for animals in WARC requires a level of focused attention as well as emotional distance. We don’t always know what’s going to happen to these animals. Often they come in injured or simply too young to survive and many do succumb. This bat was just days old and while he made it through the first night with feeding every hour or so, he didn’t make it through the second.

Caring for animals in WARC requires a level of focused attention as well as emotional distance. We don’t always know what’s going to happen to these animals. Often they come in injured or simply too young to survive and many do succumb. This bat was just days old and while he made it through the first night with feeding every hour or so, he didn’t make it through the second.  In the best of cases, they get released. Either way, the attachment of the carer can get in the way of making good welfare decisions for the sake of the animals. A certain kind of caring detachment allows for the focus to stay on the animals and their needs. Too much attachment, in some cases, can blind the carer to the best welfare for the animal.

In the best of cases, they get released. Either way, the attachment of the carer can get in the way of making good welfare decisions for the sake of the animals. A certain kind of caring detachment allows for the focus to stay on the animals and their needs. Too much attachment, in some cases, can blind the carer to the best welfare for the animal.

Our group, Krista and Ryanne, worked in the live educational display (LED) section this week at Kadoorie Farm and Botanic gardens. This means that we worked with a zoo keeper helping her with her daily tasks. Of all the animals we encountered during the day our favourite was the Macaques. This is a type of monkey that lives in the area and like many primates they are very social creatures. In the wild, they live in troops.

Our group, Krista and Ryanne, worked in the live educational display (LED) section this week at Kadoorie Farm and Botanic gardens. This means that we worked with a zoo keeper helping her with her daily tasks. Of all the animals we encountered during the day our favourite was the Macaques. This is a type of monkey that lives in the area and like many primates they are very social creatures. In the wild, they live in troops. The human-animal relationship is a complex one. In this scenario, despite being so closely related to humans, the monkeys are often not seen as being sentient and intelligent like us. Instead, once they come into conflict with humans, they are more clearly positioned on the animal side of that boundary. Yet people often lay the foundation for this conflict by encouraging the monkeys by feeding them. And when relations break down the government gets called to deal with the “problem”. The immediate solution to the problem can result in captivity and sometimes euthanasia, an outcome that is less than ideal for anyone and one that doesn’t tackle the root of the problem.

The human-animal relationship is a complex one. In this scenario, despite being so closely related to humans, the monkeys are often not seen as being sentient and intelligent like us. Instead, once they come into conflict with humans, they are more clearly positioned on the animal side of that boundary. Yet people often lay the foundation for this conflict by encouraging the monkeys by feeding them. And when relations break down the government gets called to deal with the “problem”. The immediate solution to the problem can result in captivity and sometimes euthanasia, an outcome that is less than ideal for anyone and one that doesn’t tackle the root of the problem. In addition to the monkeys’ not getting along, the way they came to be here in the first place plays a role in their future ability to be accepted by members of their own species. For example, Sita was hand raised by people as she came to Kadoorie at only two weeks old. Understandably, she prefers the company of humans rather than her fellow Macaques and one unintended consequence of saving her life is that she has to manage being bullied by the other monkeys. This is a perpetual dilemma that is constantly being negotiated in rescue work with animals.

In addition to the monkeys’ not getting along, the way they came to be here in the first place plays a role in their future ability to be accepted by members of their own species. For example, Sita was hand raised by people as she came to Kadoorie at only two weeks old. Understandably, she prefers the company of humans rather than her fellow Macaques and one unintended consequence of saving her life is that she has to manage being bullied by the other monkeys. This is a perpetual dilemma that is constantly being negotiated in rescue work with animals.